Well-designed bikeshare systems around the world have provided critical links to transit, jobs, and other destinations, thereby expanding cities’ transportation networks and connecting people to new opportunities.

1.2.1 EXPANDING SUSTAINABLE TRANSPORT THROUGH NETWORK INTEGRATION

Public Transportation

As cities consider reframing their transportation network as a service that maximizes ease and efficiency for users, opportunities emerge for bikeshare to be seamlessly integrated into the larger transit system. While this may or may not translate into increased ridership, integration between transit and bikeshare would contribute to a better, more seamless transportation network. An April 2016 study conducted by the United States Bureau of Transportation Statistics found that 77% of all bikeshare stations in the US were located within one block of another public transit mode, thereby meaningfully extending the network.[8] Bikeshare stations near bus stops were the most common transit connection; additional connectivity could be gained through on-board stop announcements that alert riders of nearby bikeshare connections, as has been implemented in Milwaukee’s buses with connections to the city’s Bublr bikeshare.

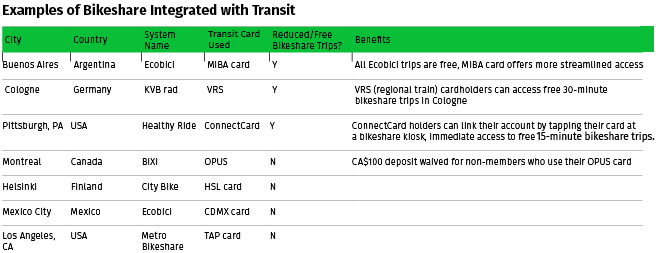

Several cities, including Los Angeles, Mexico City, and Montreal, have had success implementing “lite” transit integration, linking per trip and annual bikeshare membership payments with their existing transit cards through RFID.[9] On the “back end,” however, the user maintains two separate accounts—one for bikeshare and one for transit—each with its own payment system.

“Robust” transit integration, however, is characterized by the use of a single payment platform that enables users to access bikeshare and transit seamlessly. Bikeshare operators’ concerns about liability complicate the issue, since the transit card would need to be linked to a credit card or bank account that would be charged if a bike is damaged or stolen. Robust transit integration would enable discounted transfers to and from bikeshare, as are commonly offered between bus and rail lines, offering an alternate transportation option to help mitigate the first- last-kilometer problem. While few systems offer robust transit integration, some are moving in that direction. For example, Pittsburgh launched a transit integration pilot program in October 2017 between its Healthy Ride bikeshare and the city’s Port Authority, enabling ConnectCard users to access an unlimited number of free 15-minute bikeshare rides without setting up a separate Healthy Ride account. Transit card users are able to link their account to bikeshare by tapping their card at a Healthy Ride kiosk, and can then immediately rent a bike for free.[10]

Source: ITDP Mexico

A key aspect of elevating bikeshare to a consistently-used transportation mode is encouraging regular bikeshare use among commuters. Several systems in the US and Canada, such as in Philadelphia, Phoenix, and Vancouver, offer discounted corporate rates for employers to offer bikeshare as a commuter benefit to employees. If offering a discounted corporate rate, the bikeshare implementing agency should encourage employers to provide indoor bike storage and showers and/or changing areas to further lower barriers to cycling to work.

Major challenges to integrating bikeshare with transit arise from a lack of funding and staff time to overhaul existing or implement new technology. Bilateral coordination between bikeshare operators and city and regional transit authorities, as well as other relevant agencies is recommended to help incorporate bikeshare operations into transportation decisionmaking in a more holistic, effective way. Further, cities should take advantageof projected updates to their transit system’s payment technology as an opportunity to create links with bikeshare payment options.

Transportation Network Companies

Some transportation network companies (TNCs) have taken steps to integrate with private dockless bikeshare companies. For example, in China—with Didi Chuxing enabling users to reserve ofo bikes within their app—and India, where ride-hailing company, Ola, and car rental company, Zoomcar, have both launched integrated bikesharing pilots.[11] In San Francisco, Uber users can find and rent dockless pedal assist JUMP bikes through the Uber app. Enabling users to access rideshare and bikeshare through one app has interesting implications for shared mobility and mobility as a service. Reducing barriers to shared mobility modes makes these modes easier for users to choose and link together, offering more robust alternatives to using a private vehicle. Cities should be aware that this type of partnership could occur, and have clear data sharing requirements in place for both TNCs and bikeshare operators in order to gain insights into how and why people are using certain modes for certain types of trips.

Informal Transit

In many developing cities, informal transit modes such as cycle taxis, rickshaws and motorbikes provide affordable first-last-kilometer connections for commuters and other travelers. Depending on the size of the service area, a bikeshare system could directly compete with these informal modes—on the one hand, addressing some of the challenges brought about by informal transit such as congestion, traffic crashes, air pollution, etc., but on the other, generating conflict with existing operators if demand is not high enough to sustain them. More than likely, the unmet demand for first-last-kilometer connectivity will enable bikeshare to complement existing informal transit options.

Cities in which people rely heavily on informal transit should make a point to be transparent with existing operators about how and where the bikeshare system will operate, and discuss options for their inclusion in the system where possible—for example, creating positions to assist new bikeshare users with operating the system, and to provide security. This type of transition for informal operators has been discussed in Cairo, which plans to launch a bikeshare system in 2019. Cities can also undertake efforts to transition former informal transit operators into new jobs created by the bikeshare system’s direct operation, including in cleaning, maintenance, and rebalancing activities. Indirect employment opportunities, through the establishment of bicycle shops, bicycle tourism and related activities, may also arise.

However, while local governments should take conversations about how a new bikeshare system might impact informal transit operators seriously, the ultimate goal of bikeshare is to provide a safe, reliable, affordable transportation mode for the public, and cities should not compromise that goal to appease informal operators.

1.2.2 BIKESHARE STRENGTHENS A LONG-TERM VISION FOR CYCLING

Bikeshare can be a key component of transportation plans that include a long-term vision for cycling. Because bikeshare reduces some barriers to cycling, it can help quickly boost the number of cyclists on the road. This, in turn, can generate a political constituency that supports comprehensive infrastructure and other investments that ingrain bicycling into the transportation system. For example, in California, Santa Monica adopted a Bike Action Plan in 2011, which designated bikeshare as a high priority project toward the city’s goal to reduce vehicle trips.[12]

San Diego, California citing a goal from its legally-binding climate action plan to increase the share of bike commuters from 2% to 6% by 2020 and to 18% by 2035, is reworking its bikeshare system to better serve commuters.[13] The city relocated 15 stations, which had previously served mostly tourists along the beach, to neighborhoods more connected to public transit and biking infrastructure. At the same time, the transportation department committed to build more bike lanes and pedestrian greenways in downtown San Diego.

Rosario, Argentina passed municipal ordinance 9030 in 2012, which established the city’s public bikeshare system. Article 6 of the ordinance calls for “segregated cycle facilities” to connect bikeshare stations to one another and for these facilities to be built out as the system expands.[14] While these lanes benefit bikeshare users, they can be used by all cyclists and contribute to a safer, more comfortable riding experience. As of 2017, Rosario has 120 km of protected bike paths compared to Washington, DC, which has roughly the same area and 138 km of protected lanes (only 14.5 km of which are on-street).

Comparison of Protected Bike Lanes and Bikeshare Station Locations

Nearly all Mi Bici Tu Bici stations in Rosario, Argentina are connected by a protected bike lane (noted in dark green).

While Washington, DC’s Capital Bikeshare has many more stations, most are not adjacent to a protected lane. Source: ITDP data

Cities with (or considering) dockless bikeshare also have an opportunity to use bikeshare as a means of achieving long-term cycling goals. Greater Manchester, in the United Kingdom, allowed Mobike to begin operations as part of a smart city demonstrator in June 2017. The approval aligns with Manchester’s Cycle City program, which aims to improve air quality and public health, and reduce greenhouse gas emissions through increased bike trips. Salford, a borough of Greater Manchester, has committed to investing £10 million in bike infrastructure, and sees Mobike as a way to get more people on bikes by eliminating the commitment to maintain and store them.[15]

Data generated from bikeshare users—both historical trip data and user feedback surveys—can also provide evidence to support investments in cycling infrastructure and call for more holistic planning of cycling facilities. More details are included in subsection 4.2.2

1.2.3 CONTRIBUTING TO AN OVERALL GROWTH IN CYCLING

Often branded and brightly colored, bikeshare bikes are easy to spot around a city, contributing to increased pedestrian, transit rider, and driver awareness of the presence of bikes on the road. A study conducted by the University of Montreal of the city’s BIXI bikeshare program found that, after its second season of operation, those in the general population who were exposed to the system had a greater likelihood of cycling than those not exposed to the system.[16] By design, bikeshare also reduces or even eliminates some of the major barriers to cycling, including the cost and time required to buy and maintain a personal bike, the space needed to store a bike, and the risk of having a personal bike stolen or damaged. Without these challenges, biking becomes a viable transportation option, opening up the potential for additional connections to public transit and more convenient multi-modal trips.